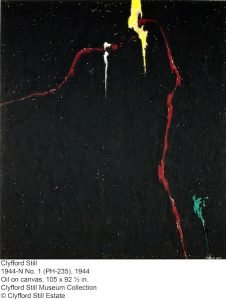

In 1944, Clyfford Still did something that no known painter appears to have done before him. Using thick, black pigment, he troweled a large canvas (105 x 92 1/2 inches) with a palette knife, then cut that textured black field, creating a deep red wound that outlined an almost organic shape. Vivid yellow seems to shine through beneath a tear, while a drip of white appears to ooze atop the blackness. In the lower right corner, a crevasse of emerald green fights for attention. There is no place for the eye to rest, and the red wound appears

to extend beyond the edge of the canvas. It’s an impending work that stops viewers in their tracks at the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver, where one views the artist’s work chronologically. Months before, Still was creating normal-sized paintings that merged human figures and machines. He was getting less literal about the human form, moving to capture the essence and spirit of life itself, and then — bam — here is this larger-than-life painting, thick, textural, and richly black, with bits of bare canvas peaking through like stars in the darkest part of a night sky. It is different than anything Still painted before and is the first of many works he would create exploring the ideas he fused for the first time in 1944-N-No. 1.

In our post-modern world, filled with endless repetitions of abstraction, the sight of a non-representational work of art continues to elicit commentary ranging from “I spilled paint on the garage floor that looked like that,” to “my two-three-four-or five-year-old could paint that.” Yet, to the discerning eye,1944-N No. 1 is more than fields of color and a few lines. The artist is playing with figure, ground, color, and texture to create something more than paint on canvas. In 1944, in the midst of WWII, a group of American artists who came to be known as the Abstract Expressionists were deadly serious about their art. Clyfford Still, perhaps the most serious, committed to preserving the purity of his work by withdrawing from the New York art world and rarely exhibiting or selling his paintings. He believed the color, texture, shapes, and forms “all fuse[d] together into a living spirit.”

While splitting his time between the East and West Coasts, Still established the basis for his original style — attributable to his Western roots. The red, vertical line in 1944-N No. 1 (and all Clyfford Still paintings) has significant meaning. Born in Grandin, North Dakota, he grew up on the prairie of Alberta, Canada. “When there were snowstorms, you either stood up and lived or lay down and died,” Still said. Another time, he stated: “My paintings have the rising forms of the vertical necessity of life dominating the horizon. For in such a land a man must stand upright, if he would live. And so born and became intrinsic this elemental characteristic of my life and work.” To Clyfford Still, his paintings merged life and death.

While splitting his time between the East and West Coasts, Still established the basis for his original style — attributable to his Western roots. The red, vertical line in 1944-N No. 1 (and all Clyfford Still paintings) has significant meaning. Born in Grandin, North Dakota, he grew up on the prairie of Alberta, Canada. “When there were snowstorms, you either stood up and lived or lay down and died,” Still said. Another time, he stated: “My paintings have the rising forms of the vertical necessity of life dominating the horizon. For in such a land a man must stand upright, if he would live. And so born and became intrinsic this elemental characteristic of my life and work.” To Clyfford Still, his paintings merged life and death.

His peers spoke of his inventiveness. Robert Motherwell said that Still’s show at Art of This Century Gallery in 1946 was the most original. A bolt out of the blue. Most of us were still working through images … Still had none.” The same year that Still created 1944-N No. 1, Rothko produced his surrealist painting Slow Swirl at the Edge of the Sea, and Jackson Pollock painted his cubist Gothic. Willem De Kooning didn’t create his first abstraction until 1945, when he painted Pink Angels, merging his Cubist and Surrealist tendencies. Mark Rothko, who wrote the introduction for Still’s exhibition, said that Still, working out West and alone, had arrived at an entirely new way of painting, incorporating forms and highly personal methods. Still came to abstraction not through European influence, but through Regionalism and Western aesthetics. Jackson Pollock said that Still made “the rest of us look academic.”

“As he [Still] himself has expressed it, his paintings are, ‘of the Earth, the Damned, and of the Recreated.’ Every shape becomes an organic entity, inviting the multiplicity of associations inherent in all living things. To me they form a theogony of the most elementary consciousness, hardly aware of itself beyond the will to live — a profound and moving experience,” Rothko wrote the same year he would break through to creating the spiritually infused, multiform abstractions he is known for, influenced by Clyfford Still.

Critics and historians also recognized Still’s originality. Irving Sandler said: “Jackson Pollock may have been the more important artist, but Still was, in my opinion, the greater innovator.” Sam Hunter called him “a remarkable and ultimately highly influential maverick” and “an independent genius.” While Clement Greenberg claimed that when he first saw a Clyfford Still painting, he “was impressed as never before by how estranging and upsetting genuine originality in art can be.” Even as late as 1976, Robert Hughes said Still was “a singular talent whose dimension will not be fully known in his own lifetime.”

Clyfford Still has been called a megalomaniac, egotistical, and difficult, but really, he was a passionate and dedicated artist. A purist. He wrote to Greenberg in 1956, acknowledging that he had set himself the seemingly impossible “task of taking painting out of academicism and all the collective traps laid down for it by the need for security in the name of rationalism, culture, aesthetics, and other conventional alibis. Inevitably, I had to violate the expectations or demands of others in painting. It was done consciously [sic] and with high purpose. And the results? — I fought for freedom to build an unlimited and ennobling instrument.”

Primal and elemental Still’s paintings seem to animate matter and invoke a life force held within an infinite space. The purpose of his art was to uplift and liberate the human soul from the limitations of the modern age — science, mechanism, power, and death. “I want the spectator to be reassured that something he values within himself has been touched and found a kind of correspondence. That being alive … is worth the labor.” And in our cynical contemporary world, we forget that this idea was once the most imaginatively original concept an artist could convey.